Innovative Teaching

NASA’s Elementary Engineers

For the past three years the students at St. Thomas More Cathedral School in Arlington not only built a satellite, but they also gained a spot through NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative to send it into orbit. Beating out businesses, universities and other NASA departments, the Arlington Catholic Diocese elementary school is one of only 16 whose satellites will launch later this year, and the school’s technology teacher Melissa Pore, who headed the program, has plans in place to share the experience with students across the globe.

The program came about a couple of years ago when Pore was developing an all-school STEM project to have a central engineering project as a focus of learning; it was “a community effort to give back and teach everyone,” she says. She had been working with the Naval Academy in Annapolis on innovative teaching strategies for STEM programs and decided to expand on her once-a-year space focus, then taught only in April. The kids devoured the class sessions on outer space, aeronautics and robotics, so she ran with the idea of incorporating one big space project spanning several years that could teach bigger ideas about “what it’s like to be an engineer in today’s world.”

Earning a grant through the Virginia Space Grant Consortium and NASA, Pore was able to give students the opportunity many intermediate-level students don’t have a chance at: real-life experiences in the classroom.

“The point of caring about STEM at all, or making a career connection, or doing a giant project as a group, is to teach beyond the textbook curriculum of yesterday and to reach out and try to entice those engineers of tomorrow. We have to create things that let the students build, modify, test [and] experiment to get them that authentic learning,” says Pore.

Pore loves to bring the world alive for her students. You don’t find her simply standing in front of a class lecturing. She’s dressed as a scientist, a drill sergeant, whatever the lesson of the day exemplifies: surface to air robotics, computer animation, coding, keyboarding boot camp, to name a few. It’s a theatrical performance that includes lights, sounds and animation. “It’s an element to surprise and grab them, to get the creative juices flowing,” she says.

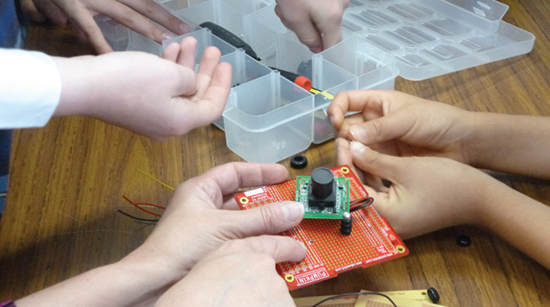

The satellite project has all 400 students at the school incorporated, from kindergartners to eighth-graders. Each student group has been exposed to all of the different parts of building the satellite, from marketing and tracking to mechanical engineers and test conductors. They even have the opportunity to Skype with the experts to ask questions about building the model. And this month, they are scheduled to speak with one of the astronauts from the International Space Station. The students built the satellite themselves; however, once the school won a spot to the space station it needed some re-engineering. The satellite is now in the final integration stage off-site.

Once the satellite is launched, the it will collect images of the Earth every 30 seconds as it flies in orbit, and each mission operation center, or one of the almost 50 other schools, will receive images of their school as it flies over.

“The goal is teaching students how to collect their images and building a big, collaborative network. Letting kids start talking about learning, talking about the world, technology, engineering. … We’re going to teach a technical skill that culminates, hopefully, in many more building projects, whatever it takes to bring them the next thing,” says Pore.

But her work does not stop with the satellite project, what she calls the “glitzy, cool one.” Pore also runs a sub club where students have been building a submarine and testing it in pools. They will compete at the Naval Academy in April for a spot to go to a national competition. She also recently received her Ham Radio license, and has garnered a call sign for the school, hoping to start a club soon. And she continues her other programs such as the Sally Ride EarthKAM project, through NASA, and invites guest speakers such as Joe Allen, a former astronaut who flew aboard Discovery and Columbia, to the school to speak with the students.

“I’m trying to bring excitement, environment, tools, and generate enthusiasm to motivate projects, learning and experiments,” says Pore. “As the technology teacher, I’m trying to create a beautiful environment for the teachers to sow their seeds.”

Engaging Minds Through Expectation

Getting a child interested in learning is not the first step in education. It’s giving teachers the confidence to take risks in their own teaching methods and to move beyond by-the-book standards to create lessons they know the students can accomplish. “The most significant factor for student achievement is teacher efficacy. Nothing else. Not class size, access to technology or even socioeconomic status has been seen in research to have as great [of] an impact on how kids learn,” says Jennifer Whiteman, art teacher at McLean’s Churchill Road Elementary. “If teachers think they can teach the kids to do it, the kids can do it.”

Over the past couple of years, Whiteman, who’s been teaching for nine, has built the necessary rapport with the teachers at the school to introduce an art-integration program that has students in kindergarten through sixth grade being assessed on cross-curriculum standards in core classes and specials, sometimes through crossover projects within subjects, other times by reinforcing in one class what is being taught in another.

“The teachers believed in me and [believed] I knew what I was doing,” says Whiteman. “Until you can get [teachers] to do that and enable them to try it and understand, there is no risk to try and get the kids to be able to do these things.”

This year’s fifth-grade class studied global societies, and instead of rote memorization, teachers incorporated a dig project where students created a civilization along with artifacts, incorporating art skills they were learning in their weekly art class taught by Whiteman. Kindergartners incorporate science in art through observation and seasons. Math is used in fourth grade through a quilting project. And the correlations continue with research and writing projects.

Whiteman says this has affected the students’ learning twofold: “They are getting more comfortable with subjects they may not have been comfortable with, and art is fun. If you can put it in a context that makes it enjoyable, that makes it fun and it makes it meaningful. … Real world problems are messy. They have writing and math and social studies and politics and context. Kids will retain more, remember it and transfer it to other types of problems because they’ve learned the skill in context.”

Identifying a set of art skills for each grade level is what made this possible. Whiteman founded a Curriculum Integration of the Arts Team at the school where the group of teachers develop projects that implement integrated curriculum, set expectations for student work, and establish common vocabulary. Teachers in any subject now hold higher expectations of the student’s capabilities across the board with any project. But it still has to start with teacher efficacy.

“Sometimes it’s the fear of taking the risk and expecting too much,” says Whiteman. “[A teacher will fear that they’ve] pushed too far and the students won’t be able to do it. Then you’ll have a class of sobbing first graders that can’t stitch, which has happened to me. But you learn from that. You know they can do it. It’s just figuring out what do I need to do to help them learn it.”

Moving Mathematics

Imagine walking into a math class and seeing that there are no desks. No pencils. No worksheets. Instead, stories are told and acted out. In one lesson children may be bears fishing in a lake to work out a math problem; given a mathematical story equation, children bear crawl to the lake and count out how many fish they will eat. In another, they are frogs sharing lily pads. This is the setting at Columbia Elementary School in Annandale, where physical education teacher and specialist Jason Kain works with second graders who have been pinpointed by their homeroom teachers for extra help in math.

“Children need blood to the brain to learn. They need to move,” says Kain. “What we’re doing is getting blood flowing back to the brain to get them to be able to think better. They’re engaging in a physical activity that matches the standard they are doing in PE, and they are simultaneously working on math, literacy, or whatever they need.”

Google Docs that explain the standards students work on in class are created by the classroom teachers and shared with Kain. Kain, in turn, shares ideas for a connected activity and teachers choose students they think will gain the most from the activity. “Teachers choose the kids they think are going to be the most excited here, most successful, that are going to develop a love and joy of math from being here,” says Kain.

Programs like this are sprinkled throughout the school, utilizing PE, music, art and library to garner a broader understanding of subjects through kinesthetic, auditory and visual learning styles. And even though it is the first year of the program, Principal Michael Cunningham says the teachers are already seeing the benefits.

“What we’re finding with this is, because we’re using different learning styles, the teachers are really commenting on ‘They get it’ because [the students] have done it in a different way. … You know the definition of insanity … this is giving us a different way, and the kids seem to be picking up the information,” he says.

Kain, in his first year of teaching—he is a career-switcher who has a doctorate in industrial and organizational psychology—developed his teaching philosophy as one that uses theory to connect PE and classroom standards, “incorporating everything I can because the world doesn’t work in isolation.”

Last year he brought his Academic Movement idea to Annandale Terrace Elementary one day a week when he would go into math classes to work with the entire class. This past summer Kain presented at the Health and Physical Activity Institute at James Madison University.

Currently, Kain’s classes at Columbia are part of the school’s intervention program for second graders, but Cunningham’s goal is to bring it to any student who needs the additional help, not just those in a certain grade level.

Mindful Thinking Brings Self-Aware Students

“Spaghetti!” Twenty-four 5- and 6-year olds immediately sit taller, cross-legged, on the floor of the kindergarten class. Backs go straight; muffled sounds quiet; their hands go to their bellies. They are practicing mindfulness, a mental calming technique that is finding its way into classrooms across the nation and at Pinecrest School in Annandale.

The spaghetti pose is just one of many prompts to get children to calm down, focus and pay attention to the now. “We are supporting the culture change that we are hoping to influence,” says Mary Beth Quick, founder of Heart and Soul Yoga LLC, who brought the mindfulness and yoga program to Pinecrest, and set up similar programs at Woodson High School and other elementary schools in Fairfax. “We are helping students build their toolbox to help increase their resilience and emotional intelligence … that it’s not just the academics that are important, that it’s important to deal with life as it comes at you and be resilient as you are going through it.”

Since last school year, Pinecrest has been talking with Quick about bringing the practice of mindfulness to 62 kindergarten through sixth-grade students. Beginning this fall, they were able to put their plans into action with weekly sessions that had students paying attention to their bodies, their emotions and how to control reactions in any given situation. Fifth-grade students at Pinecrest say they have already seen the benefits and even use mindfulness techniques outside of the classroom. Noah, 10, was playing a game in PE. When his team lost he says he didn’t care but that the winning team players were sore winners. He got mad but decided to use his “anchor breaths: I opened my eyes and did what I was supposed to.” Chase, 11, got really angry one night at home and used “heartfulness and sent a message to myself to calm down. It settled my nerves.”

Nicole McDermott, principal of Pinecrest, says the program is aligned with the school’s mission—“focusing on social, emotional growth as much as on academic growth; helping the students really think about how they feel, understanding how their feelings affect their actions and how those actions affect being part of a community”—and while at first there was concern about devoting instruction time to the program, the teachers have seen the positive effects throughout the school.

Kindergarten teacher Heather Vogus says the biggest benefit in her class is when kids get riled up, or have a difficult time transitioning from one event to another, or they need a break; “It gives them a pause and helps them refocus.” But it’s not just in the classroom. “It’s a school-wide tool; I can use it with any student. Having it done school-wide is a huge benefit. Every kid here knows it and bought into it.”

With today’s rigorous lifestyles, it’s necessary to teach children coping mechanisms. Instructing them at a young age to take a moment to think before they act, or to be more aware of how they feel and why they feel a certain way, will only benefit them in the classroom and in their future. “Take a breath; take a pause. If you can learn that at age five, you are in a much stronger position going into the world,” says McDermott.

(March 2015)